Getting started with the Jupyter Notebook#

Welcome to this introduction to Jupyter Notebooks! The advantage of notebooks is that they can include explanatory text, code, and plots in the same document.

This makes notebooks an ideal playground for explaining and learning new things without having to jump between several documents. Thanks to JupyterHub, you can run them in your web browser without requiring to install anything!

This document itself is a notebook. It is a simple text file with a .ipynb file path ending. If you opened this notebook via classroom.oggm.org, it is opened in a platform which is called JupyterLab. “JupyterLab” is the development environment allowing you to navigate between notebooks (navigation bar on the left), (re-)start them, and much more. Here, we will focus on the notebooks themselves.

First steps#

At first sight the notebook looks like a text editor. Below this line, you can see a cell. The default purpose of a cell is to write code:

# Click on this cell, so that its frame gets highlighted

m = 'Hello'

print(m)

Hello

You can write one or more lines of code in a cell. You can run this code by clicking on the “Run” button from the toolbar above when the cell’s frame is highlighted. Try it now!

Clicking “play” through a notebook is possible, but it is much faster to use the keybord shortcut instead: [Shift+Enter]. Once you have executed a cell, the next cell is selected. You can insert cells in a notebook with the + button in the toolbar. Again, it is much faster to learn the keybord shortcut for this: [Ctrl+m] or [ESC] to enter in command mode (blue frame) then press [a] to insert a cell “above” the active cell or [b] for “below”.

Create a few empty cells above and below the current one and try to create some variables. Instead of clicking on a cell to enter in edit mode press [Enter].

You can delete a cell by clicking “Delete” in the “Edit” menu, or you can use the shortcut: [Ctrl+m] to enter in command mode then press [d] two times!

More cell editing#

When you have a look into the “Edit” menu, you will see that there are more possibilities to edit cells, like:

copy / cut and paste

splitting and merging cells

and more.

a = 'This cell needs to be splitted.'

b = 'Put the cursor in the row between the variables a and b, then choose [split cell] in the "Edit" menu!'

Another helpful command is “Undo cell operation’, which is sometimes needed when the double key [d][d] was pressed too fast.

Writing and executing code#

The variables created in one cell can be used (or overwritten) in subsequent cells:

s = 'Hello'

print(s)

Hello

s = s + ' Python!'

# Lines which start with # are not executed. These are for comments.

s

'Hello Python!'

Note that we ommited the print commmand above (this is OK if you want to print something at the end of the cell only).

In jupyter notebooks, code autocompletion is supported. This is very useful when writing code. Variable names, functions and methods can be completed by pressing [TAB].

# Let's define a random sentence as string.

sentence = 'How Are You?'

# Now try autocompletion! Type 'se' in the next row and press [TAB].

# Call methods of the string by typing "sentence." and pressing [TAB].

# Choose for example the method lower() and see what happens when you execute the cell!

sentence.lower()

'how are you?'

An advantage of notebooks is that each single cell can be executed separately. That provides an easy way to execute code step by step, one cell after another. It is important to notice that the order in which you execute the cells is the order with which the jupyter notebook calculates and saves variables - the execution order therfore depends on you, not on the order of the cells in the document. That means that it makes a difference, whether you execute the cells top down one after another, or you mix them (cell 1, then cell 5, then cell 2 etc.).

The numbers on the left of each cell show you your order of execution. When a calculation is running longer, you will see an asterisk in the place of the number. That leads us to the next topic:

Restart or interrupt the kernel#

Sometimes calculations last too long and you want to interrupt them. You can do this by clicking the “Stop button” in the toolbar.

The “kernel” of a notebook is the actual python interpreter which runs your code. There is one kernel per opened notebook (i.e. the notebooks cannot share data or variables between each other). In certain situations (for example, if you got confused about the order of your cells and variables and want a fresh state), you might want to retart the kernel. You can do so (as well as other options such as clearing the output of a notebook) in the “Kernel” menu in the top jupyterlab bar.

Errors in a cell#

Sometimes, a piece of code in a cell won’t run properly. This happens to everyone! Here is an example:

# This will produce a "NameError"

test = 1 + 3

print(tesT)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[9], line 3

1 # This will produce a "NameError"

2 test = 1 + 3

----> 3 print(tesT)

NameError: name 'tesT' is not defined

When a cell ends with an error, don’t panic! Nothing we cannot recover from. First of all, the other cells will still run (unless they depend on the output of the failing cell): i.e., your kernel is still active. If you want to recover from the error, adress the problem (here a capsize issue) and re-run the cell.

Working with numpy#

You might have read somewhere that Python is “slow” in comparison to some other languages. While generally true, this statement has only little meaning without context. As a scripting language (e.g. simplify tasks such as file renaming, data download, etc.), python is fast enough. For numerical computations (like the computations done by an atmospheric model or by a machine learning algorithm), “pure” Python is very slow indeed. Fortunately, there is numpy to overcome this problem!

Numpy was specially developed to minimise the overhead of python and under the hood uses optimized C-code for mathematical operations. Further operations are vactorized for arrays, meaning (if appropriate) the operation is applied at once to all elements of the array. And finally numpy comes with many common mathematical operations ready to use.

Let’s have a look:

# first we need to import numpy

import numpy as np

# now we can define large arrays

test_array = np.linspace(1,100, 100)

# and we can do mathematical operations

# like sum up

test_array + test_array

array([ 2., 4., 6., 8., 10., 12., 14., 16., 18., 20., 22.,

24., 26., 28., 30., 32., 34., 36., 38., 40., 42., 44.,

46., 48., 50., 52., 54., 56., 58., 60., 62., 64., 66.,

68., 70., 72., 74., 76., 78., 80., 82., 84., 86., 88.,

90., 92., 94., 96., 98., 100., 102., 104., 106., 108., 110.,

112., 114., 116., 118., 120., 122., 124., 126., 128., 130., 132.,

134., 136., 138., 140., 142., 144., 146., 148., 150., 152., 154.,

156., 158., 160., 162., 164., 166., 168., 170., 172., 174., 176.,

178., 180., 182., 184., 186., 188., 190., 192., 194., 196., 198.,

200.])

# calculate the mean

np.mean(test_array)

50.5

# calculate the median

np.median(test_array)

50.5

# calculate the squareroot

np.sqrt(test_array)

array([ 1. , 1.41421356, 1.73205081, 2. , 2.23606798,

2.44948974, 2.64575131, 2.82842712, 3. , 3.16227766,

3.31662479, 3.46410162, 3.60555128, 3.74165739, 3.87298335,

4. , 4.12310563, 4.24264069, 4.35889894, 4.47213595,

4.58257569, 4.69041576, 4.79583152, 4.89897949, 5. ,

5.09901951, 5.19615242, 5.29150262, 5.38516481, 5.47722558,

5.56776436, 5.65685425, 5.74456265, 5.83095189, 5.91607978,

6. , 6.08276253, 6.164414 , 6.244998 , 6.32455532,

6.40312424, 6.4807407 , 6.55743852, 6.63324958, 6.70820393,

6.78232998, 6.8556546 , 6.92820323, 7. , 7.07106781,

7.14142843, 7.21110255, 7.28010989, 7.34846923, 7.41619849,

7.48331477, 7.54983444, 7.61577311, 7.68114575, 7.74596669,

7.81024968, 7.87400787, 7.93725393, 8. , 8.06225775,

8.1240384 , 8.18535277, 8.24621125, 8.30662386, 8.36660027,

8.42614977, 8.48528137, 8.54400375, 8.60232527, 8.66025404,

8.71779789, 8.77496439, 8.83176087, 8.88819442, 8.94427191,

9. , 9.05538514, 9.11043358, 9.16515139, 9.21954446,

9.2736185 , 9.32737905, 9.38083152, 9.43398113, 9.48683298,

9.53939201, 9.59166305, 9.64365076, 9.69535971, 9.74679434,

9.79795897, 9.8488578 , 9.89949494, 9.94987437, 10. ])

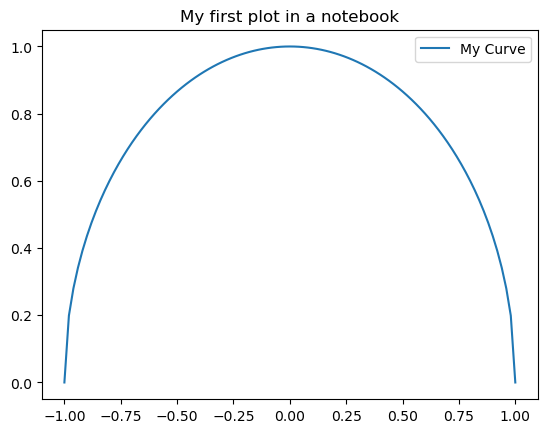

Displaying plots with matplotlib#

The most widely used plotting tool for Python is Matplotlib. Its syntax is inspired from Matlab and might be familiar to a few:

# We import matplotlib:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Let's plot something nice:

# Define a square function of x using numpy again

x = np.linspace(-1, 1, 101)

y = np.sqrt(1-x**2)

# Plot it.

plt.plot(x, y, label='My Curve')

plt.title('My first plot in a notebook')

plt.legend();

For advanced users: interactive plots with Bokeh#

Bokeh is a plottling library made for the web. It uses another syntax than matplotlib and can be used to display interactive plots. We sometimes prefer to use interactive plots as they allow to explore the data after plotting. Here is an example:

# hvplot is a plotting library relying on bokeh

# you'll need to install it alongside with pandas for this cell to work

import hvplot.pandas

# pandas is a very useful data analysis library, we will have a closer look in the next tutorial

import pandas as pd

# This makes the plot

ts = pd.Series(index=x, data=y)

ts.hvplot().opts(title='An interactive plot', width=500)

Formatting your notebook with text, titles and formulas#

The default role of a cell is to run code, but you can tell the notebook to format a cell as “text” by clicking in the menu bar on “Cell”, choose “Cell Type” \(\rightarrow\) “Markdown”. The current cell will now be transformed to a normal text.

Again, there is a keyboard shortcut for this: press [Ctrl+m] to enter in command mode and then [m] to convert the active cell to text. The opposite (converting a text cell to code) can be done with [Ctrl+m] to enter in command mode and then [y].

As we have seen, the notebook editor has two simple modes: the “command mode” to navigate between cells and activate them, and the “edit mode” to edit their content. To edit a cell you have two choices:

press

[enter]on a selected (highlighted) celldouble click on a cell (any cell)

Now, try to edit the cell below!

A text cell is formatted with the Markdown format, e.g. it is possible to write lists:

item 1

item 2

Numbered lists:

part a

part b

Titles with the # syntax (the number of # indicating the level of the title:

This is a level 3 title (with 3 # symbols)#

Mathematical formulas can be written down with the familiar Latex notation:

You can also write text in bold or cursive.

Download a notebook#

Jupyter notebooks can be downloaded in various formats:

Standard notebook (

*.ipynb): a text file only useful within the Jupyter frameworkPython (

*.py): a python script that can be executed separately.HTML (

*.html): an html text file that can be opened in any web browser (doens’t require python or jupyter!)… and a number of other formats that may or may not work depending on your installation

To download a jupyter notebook in the notebook format (.ipynb), select the file on the left-hand side bar, right-click and select “Download”. Try it now!

For all other formats, go to the “File” menu, then “Export notebook as…”

Take home points#

jupyter notebooks consist of cells, which can be either code or text (not both)

one can navigate between cells in “control mode” (

[ctrl+m]) and edit them in “edit mode” ([enter]or double click)to exectute a cell, do:

[shift+enter]the order of execution of cells does matter

a text cell is written in markdown format, which allows lots of fancy formatting

These were the most important features of jupyter-notebook. In the notebook’s menu bar the tab “Help” provides links to the documentation. Keyboard shortcuts are listed in the “Palette” icon on the left-hand side toolbar. Furthermore, there are more tutorials on the Jupyter website.

But with the few commands you learned today, you are already well prepared for the OGGM-Edu experiments!

What’s next?#

visit the next tutorial: A OGGM Workflow Intro