It was a long process, but our model description paper is finally published on Geoscientific Model Development. Thanks to two very positive reviews, it became one of the highlight articles in GMD and is already one of the top downloaded paper of the last 12 months.

These are great achievements, and we would like to thank everyone involved: people who contributed ideas and time to the project, reported bugs, or criticized it. Feedback (positive or negative) is what makes such a project live and move forward!

I would like to take this opportunity to reflect about the status of the project, as well as about the challenges ahead of us, both scientific and organisational. I tried to keep this discussion as general as possible, leaving technical details for other platforms.

Features

We now have a model able to simulate the dynamics of any single glacier of the world. This alone isn’t new: let’s highlight some of the features that makes the OGGM project unique.

Automated workflow

The entire model chain (from pre-processing to dynamical runs) is fully automatized and reproducible by anyone with an internet connection and a computer able to run a python script.

Most global models I’m aware of are built on a step-by-step, ad-hoc model chain, where processing steps are independent from each other or even written in different programming languages (for example GloGEMflow, which is partly written in IDL and in Matlab).

“Automated” means that people can jump in at any step of the modelling chain and use the generated data (topography, climate, flowlines…) for their own workflow. Our input data are downloaded by OGGM “on the fly”, from their original open repositories. For some users, OGGM might simply be used as a way to get data processed in a traceable way, for example for model inter-comparisons using homogenized boundary conditions.

Open source

The entire OGGM codebase (including all its satellite projects) is available under an open source, free software license. Anyone can download, adapt, and share adaptations of this work as they wish.

Modular

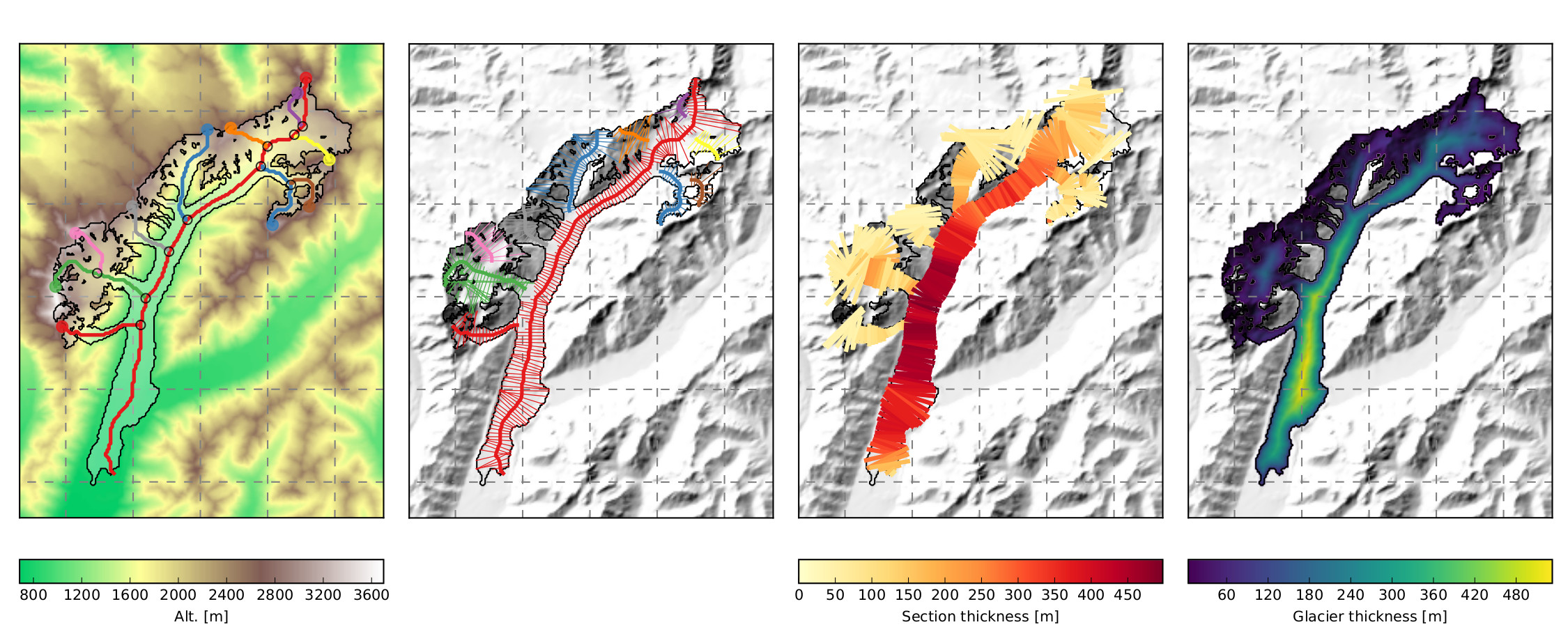

OGGM is able to (i) provide a local map of the glacier including topography, (ii) estimate the glacier’s total ice volume and compute a map of the bedrock topography, (iii) compute the surface climatic mass balance, and (iv) simulate the glacier’s dynamical evolution under various climate forcings. For each of these steps, several choices are possible regarding the input data to be used, the numerical solver, or the parameterizations to be applied. Any given choice is driven by subjective considerations about data availability, the estimated accuracy of boundary conditions, and by technical considerations such as the computational resources available.

In OGGM we propose at least one way to realize these steps. However, the OGGM software is built in such a way that new approaches can be implemented, tested, and applied at minimal cost by the community.

Opportunities

Back in 2015, when Ben and I discussed the idea behind OGGM, I sometimes wondered: what’s the point? We are going to build a model, apply it once or twice, and that’ll be it.

Today, I have to admit that I was completely wrong. More than five research proposals have been funded on the basis of OGGM, and more will come. Several graduate students are working with the model and either submitted their first study, or are about to do so. We created an educational platform based on OGGM, and new users are reporting problems to our issue tracker (yes, this is a good thing as well!).

When we started, we didn’t know if global scale glaciology will continue to be relevant, or if python would continue to grow as the primary computer language of science. It appears we were right: I see a bright future for the model, but I also see some challenges ahead…

Scientific challenges

Many people are now applying the model, with its default configuration. This is understandable, because applying a model to answer a scientific question is what scientists are supposed to do. However, very little has been done to assess the uncertainty of OGGM yet. There is currently no tool, no automated workflow available to assess the accuracy of the numbers out model produces. Doing so in a general way requires a great deal of thinking, and we currently ask our users to do their assessment. It is a pressing task to provide more tools to help users in calibrating and evaluating the model.

Furthermore, we will have to continue the development of new modules for physical processes currently unaccounted for in the model. In particular: improved parameterizations for radiation, surface albedo, surface debris, frontal ablation… All this will require more data sources for calibration and validation. In particular, we are currently not making use of the many geodetic mass-balance data based on satellite products.

Organisational challenges

Developing an open-source model involves much more commitment than just “put your code online”. Our goal is to engage a community of both users and developers, which means that we are committed to:

- provide a comprehensive documentation for new and returning users

- test our code in a continuous and transparent manner

- not changing the model internals or API without notice, and only if really necessary

- provide support to users and acknowledge bug reports

- engage the community and encourage further model enhancements

All of this costs a lot of time. And, unfortunately, time spent on project maintenance and management is not rewarded in academia. I encourage our graduate students to participate in the maintenance, but I also tell them that they cannot spend too much time on it, because publications have to come first.

Furthermore, I’ve noticed that the learning curve of the model is steeper than I thought. I tend to forget how much time it takes to gain up speed with advanced programming concepts such as object oriented programming, testing, and design patterns. Most scientists have no formal training in programming, and have to learn these skills by themselves. This is only possible with a lot of commitment and a genuine interest.

All these obstacles and lack of time make it harder for people to contribute to the model. Some improvements are not making it to the codebase because it would take one or two more days of work, without immediate rewards.

Conclusions

We have done so much already, and we can be proud of what we’ve achieved so far! But we also have a lot of work ahead: widening the user base and acceptance of the model will need time and commitment.

I believe that we are on the right track!