For decades, the Hintereisferner glacier in the Austria’s Ötztal Alps, has been the key research site for glaciological studies of the Department of Atmospheric and Cryospheric Sciences (ACINN) at the University of Innsbruck. Length measurements exist for around the last 150 years and mass-balance measurements (amount of mass a glacier gains and loses over a year) for roughly 70 years. There have also been many local-scale projects on the glacier. For example, a permanent terrestrial laser scanner was recently installed to identify snow (re)distribution (Voordendag et al, 2021).

Below is a webcam image of the Hintereisferner on June 21, 2022:

So far, the 2022 melt season started on an exceptional note: in June, Hintereisferner has already lost most of its protecting snow cover. In the 4 preceding years from where we have webcam images available, Hintereisferner always had much more snow left in June. Check it out by clicking on the image and changing the years on the webcam webpage!

There is also a press release (only in German) that describes more in details the early “Glacier Loss Day” (June 22nd) of the melt season 2022 for the Hintereisferner. The Glacier Loss Day is the day where the glacier has lost already all the mass that it gained over the winter. For Hintereisferner, it has never been recorded to be that early in the year.

Although the OGGM community here in Innsbruck works on large-scale glacier modelling, we still have a special relationship with the Hintereisferner: Hintereisferner is often used as a test glacier to regularly check our existing code and when starting a new workflow, we use Hintereisferner as the first test before repeating it on many other glaciers. In addition, many of us have contributed to mass-balance measurements on the glacier. Here is a German article with some nice pictures from one of these measurement campaigns.

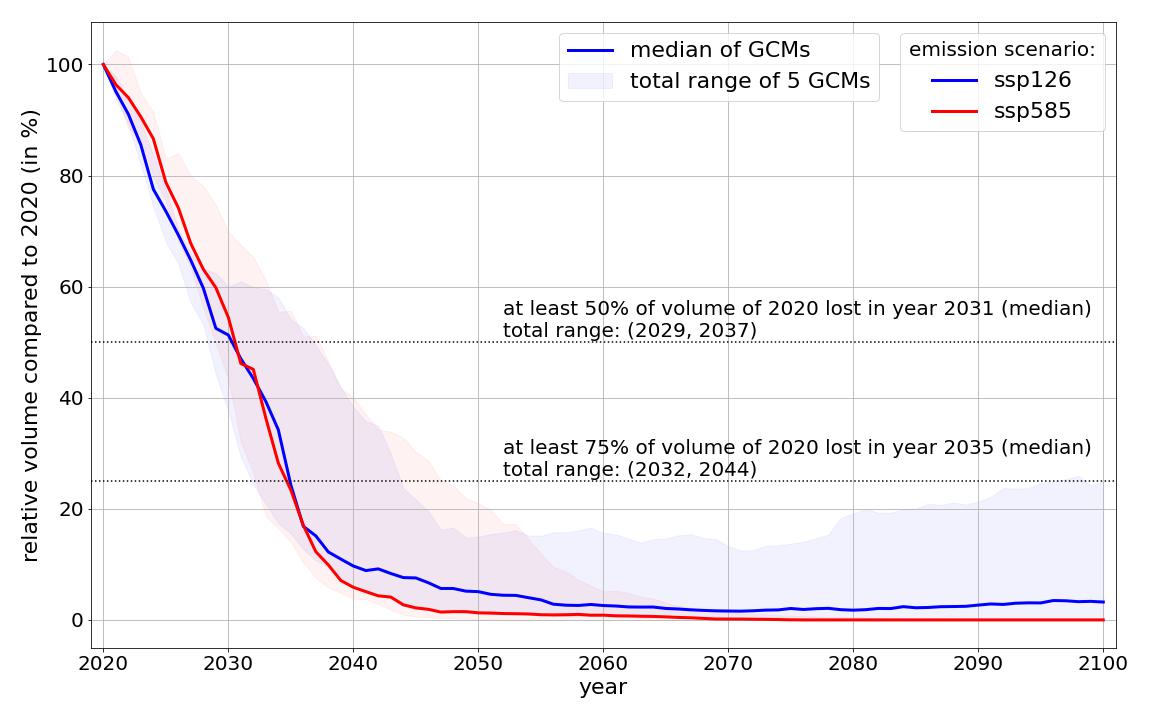

In recent months, I have recognized, that for Hintereisferner and many other reference glaciers with additional observational data, the model predicts very fast melting rates in the near future. This means that by the time we reach the year 2100, many reference glaciers are almost - or even completely - lost. I am interested in comparing the influence of different mass-balance model options on the projections: if the glaciers are gone, it does not matter which mass-balance model we choose and the difference between the options are of course zero. After some discussions with Dave, we thought about another way to compare the options, i.e. the year where half of a glacier’s volume is lost. When I computed that year, it was a bit shocking.

When will Hintereisferner lose 50% of its 2020 volume?

According to the model, Hintereisferner loses 50% of its volume from 2020 to 2031. In those 11 years, the glacier is projected to lose around 5% of its glacier volume every year.

During the next meeting with my supervisors, Fabien and Dave, I showed them the numbers and a similar plot to the one below:

Relative volume change projections compared to 2020 for the Hintereisferner glacier, Ötztal Alps, Austria

Fabien was a bit sceptical, asking “Are you sure that this is Hintereisferner?”.

Checking my code again…

Of course, the numbers had made me suspicious as well. And, yes, it is the Hintereisferner. To have more robust estimates, I repeated my computations for 5 different climate projection models (i.e. GCMs) and for two emission scenarios using the newest available data and model options (see the plot above). The low emission scenario (ssp126) corresponds to a global warming of around 1.8°C in 2100 and the high emission scenario (ssp585) to a global warming of around 4.8°C compared to preindustrial times (click here). Volume changes similarly for the two emission scenarios, because Hintereisferner is reacting to past and near-future climate change which is independent of the emission scenario. For 4 out of the 5 GCMs, in 2031 or earlier, 50% of the volume is projected to be lost, while for the remaining 1 GCM, half of the volume is just lost by the year 2037. Because of this outlier GCM, I have opted to show the median volume estimates. It shows the central tendency more robustly compared to using an average value. So, overall, the scenarios and GCMs agree consistently on the near-term projections. And, unfortunately, I have not (yet) found any coding error! At least, if we reduce our emissions fast enough, some ice patches of Hintereisferner might be left by 2100.

What do you think?

How much time is left until Hintereisferner gets too small to be used as Open Air Laboratory?

For those interested in more methodological details:

For these estimates, I used simple methods that could be applied to any glacier in the world. To model the mass-balance over the glacier, I used a variant from the default mass-balance model option that is currently under development in the OGGM package: massbalance-sandbox. That means that surface type distinction is included to distinguish between melt factors of ice and snow. In addition, a variable temperature lapse rates instead of a constant value is used. I have uses W5E5 (Lange et al., 2019) as the past climate dataset and the 5 GCMS from the ISIMIP3b (Lange & Büchner, 2021) projections for the future climate, both on a daily resolution. For the projections that I have shown, I calibrated the glacier to match the geodetic observations of Hugonnet et al. 2021. The precipitation has been corrected by a precipitation factor that depends on the winter precipitation amount of that glacier.

This was just a side story of my actual research: the influence of different mass-balance model and calibration options on glacier change projections for reference glaciers (Schuster et al., in preparation).