I have been invited to give a talk at AGU 2021, for the newly created session C51A: “Community Tools and Products for Cryosphere Discovery and Application”. This session showcases fantastic contributions from the cryo community, and I am honored to be able to provide some insights from our experience with OGGM, so that similar projects can build upon these ideas and make a better job than we did.

This year’s AGU is taking place in a hybrid online / presence format, and unfortunately I won’t be able to attend in person. Let’s take this opportunity to experiment on a new format, the blalk.

“Blalk”: portmanteau word blending “blog” and “talk”

If you are more of the “listening” type, here is the video recording of the presentation. It’s not my best performance though, so you might just want to grab some links and tips in the post below.

I recommend to play the video at faster speed if you are in a hurry. Here are the slides.

Take home messages

- Thanks to the open-source community, building scientific software documentation has never been so easy. Feel free to use the OGGM repositories as a template for your project.

- Even the best documentation won’t prevent misunderstandings and disappointments. Be prepared for long-term support.

- Open-source and open-science take time! We need a fundamental change in the traditionally valued skills in academia, to better reward open science practices and improve code literacy.

The ingredients of Open Science

- Transparency: content/code on GitHub/GitLab with an open license allowing reuse and open review.

- Reusability: documentation, tests, support.

- Reproducibility: installation instructions and computational environments capsules (e.g. MyBinder, Jupyter-Hub).

Science software documentation made easy

The OGGM online documentation is built around four components: the project website for a general audience, the static documentation for potential and returning users, the interactive tutorials for active learning, and a forum for community exchange.

Thanks to fantastic volunteers from the Python and Jupyter communities, we can rely on a suite of open source tools to help us build each of these elements (relatively) easily.

Project website: oggm.org

It is this webpage and the entry point for people who don’t know yet about the model. It provides links to the documentation/tutorials and, importantly, it hosts a blog where we share updates about new releases, job announcements, workshops, or papers.

A project website is “nice to have”, but not a real necessity: if you have to skip one thing in your documentation strategy, it is probably this one.

Tech details: the website is written in the markdown lightweight markup language and built using the Jekyll static site generator. It is hosted for free on github pages, and we are paying a few € per year for the oggm.org domain to point to it. The code for the website can be found on this github repository.

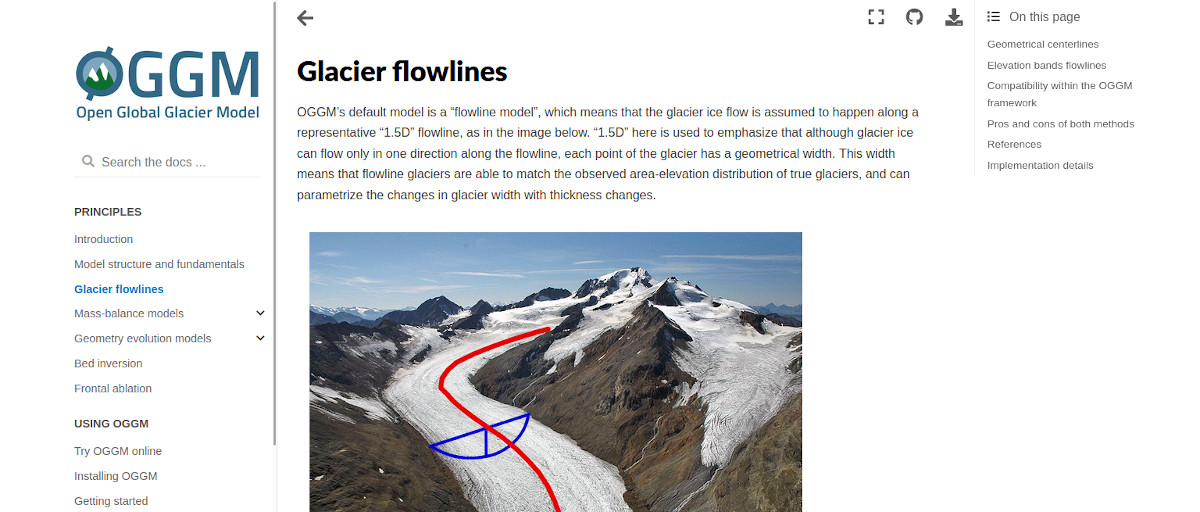

Static documentation: docs.oggm.org

The model documentation contains high-level information about the model physics and assumptions, as well as a comprehensive listing of model functions and implementation details. It is targeting potential as well as returning users looking for information. This documentation is written and hosted alongside the python code. It is generated automatically when the code is updated, and we ask OGGM contributors to also write a bit of documentation.

Tech details: the static documentation is created with the Sphinx documentation software. It is written in the reStructuredText markup language for the landing pages and with numpydoc for the python function descriptions. It is generated and hosted for free on Read The Docs, and we are paying a few € per year for the docs.oggm.org domain to point to it. The OGGM static documentation code is found in the same repository as the OGGM python code.

Interactive tutorials: oggm.org/tutorials

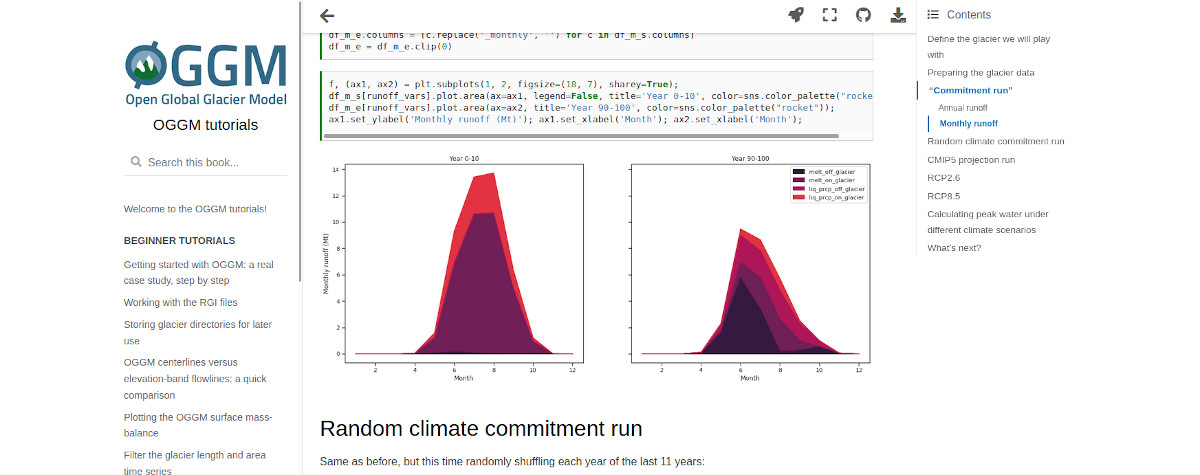

Learning by doing! The OGGM tutorials are a collection of jupyter notebooks which combine code, plots, and narrative text. They guide users through the steps required to realize a certain task, for example producing and analyzing model output. The notebooks are available as a compilation of a static webpages for online reference, but they are best used when run in interactive mode. Thanks to the MyBinder online service, we are able to provide interactive sessions which allow anyone to run OGGM “on the cloud”! The possibility to run a model without any installation isn’t only a commodity, it allows scientists and students with limited computer skills or resources to try the model online before going the hurdle of installing OGGM.

Tech details: the tutorials are written in jupyter notebooks. They contain valid OGGM code that can be executed alongside narrative text and equations for explanation. The notebooks are executed and compiled into a website with jupyter book (we do this automatically thanks to github actions, but you don’t have to). Users can run the notebooks in interactive sessions for free, either via MyBinder (temporary sessions, no registration) of via OGGM Hub (permanent sessions, we’ll have to create a user for you). The OGGM tutorials can be found on this github repository.

User forums: Github and Slack

For Q&A and project discussions, we rely on github issues (for bug reports or usage questions) and Slack (for usage questions and chitchat). Slack is not open source and I wish we could rely on fully open discussion forums such as Discourse, but experience shows that many people are very reluctant to ask questions in open channels. This is probably by fear of asking “something stupid” online, or because they are reluctant to create yet another account on an unknown platform. Since many people use Slack at work nowadays, the OGGM Slack channel has become the main platform where the community exchanges questions and ideas.

Is it really that easy?

It may sound like a lot of new tools and information, but if you go step by step you will notice that each of these tools is relatively easy to use if you are willing to spend some time learning them. They are made by and for scientists (not computer scientists), and make building documentation look fun and easy! It was so much fun that we decided to also use these tools for educational purposes with the platform OGGM-Edu, which I invite you to visit as well!

The best way to get started is to check for a project you like (for example OGGM ;-), and use this as a template.

Be prepared for long-term support

Opening code is one thing; actually making it reusable and reproducible is another.

Don’t get me wrong! Open code is fantastic, and it should be standard for all scientific publications to be accompanied by the code used to produce the presented results. What I mean is that providing code that will be used by others has a much higher cost, which I want to dig into here.

The obvious cost of writing documentation

This may sound trivial, but it still deserves a mention: even with all the fabulous tools listed above, writing documentation takes time, energy, and a lot of thought. It also requires discipline, since each new feature should in theory also be described somewhere (otherwise it might get forgotten).

The invisible cost of maintenance and support

Once people start to install and use a software, its developers need to make sure that it produces the same expected output for each environment. In the OGGM codebase, for every 100 lines of code, 40 additional lines are written for tests. Another 40 lines are written as text-based documentation. Therefore, small changes in a model functionality can lead to a series of changes in the documentation, the tests, the tutorials, and may have unknown unknown impacts on user-written scripts.

There is a permanent tradeoff between “agility” (the freedom to change code when new ideas come in) and “backwards compatibility” (the large amount of code, tests, tutorials that might be affected by a cool new idea).

It is reasonable to ask if these costs are “worth” the added value of sharing code.

The curse of modularity

One of OGGM’s central objectives (“raison d’être”) is to allow several model configurations to be tested and compared against each other. This also comes at a cost: when new parameterizations are added to the pool, the old ones stick around. User are also allowed to expect that the functionalities they wrote will work in the future. All of this leads to a lot of “technical debt”, code that works but that you would write much differently today.

It is reasonable to ask if you won’t be better off by NOT making your code modular, and focus on what matters most for the advancement of a project (at the cost of backwards compatibility).

Expectations versus reality

Like many of the models in cryospheric sciences, OGGM is a “niche” model. Indeed, OGGM alone cannot simulate all components of ice flow, the compaction of snow, or the subsurface flow of meltwater. OGGM has one main purpose: simulate the evolution of many glaciers in data-scarce situations, and to simulate them fast.

With this design, OGGM will only be used by a handful of working groups worldwide. Maybe more than a dozen, but definitely not hundred. If I am completely honest, the amount of documentation around OGGM is quite exaggerated given its comparatively small audience. One of the reasons for this apparent imbalance is that I have a lot of fun designing the OGGM ecosystem and its documentation. Another reason is that I wish OGGM to set a “standard” and offer a template that other projects can build upon.

These high standards (documentation, tests, online tools…) may raise expectations of external readers. With all this information, it will take time for a newcomer to realize what is possible to do with OGGM and what isn’t. Which applications are suitable for the model, and which aren’t.

When discovery a new tool online, it is reasonable to ask whether this tool really is useful for your use case, or if it is just very “shiny”.

Documenting a highly parameterized model

Let’s try to make a parallel between a “niche” model like OGGM and a widely used atmospheric model such as WRF.

WRF is used by thousands of scientists worldwide. Yet, the WRF documentation is incredibly spars with respect to the model physics and internals. In fact, most of the WRF documentation is targeting the successful installation and running of the model, not really “how it works”. I think that people don’t need that kind of documentation because WRF is trusted to simulate the atmosphere accurately enough with its default settings. Users (not necessarily atmospheric scientists) can download the model, change the boundary conditions and simulation domain, and make new discoveries with it. They trust the model because they can evaluate its output, for example with independent in-situ observations, radio soundings, and satellite data.

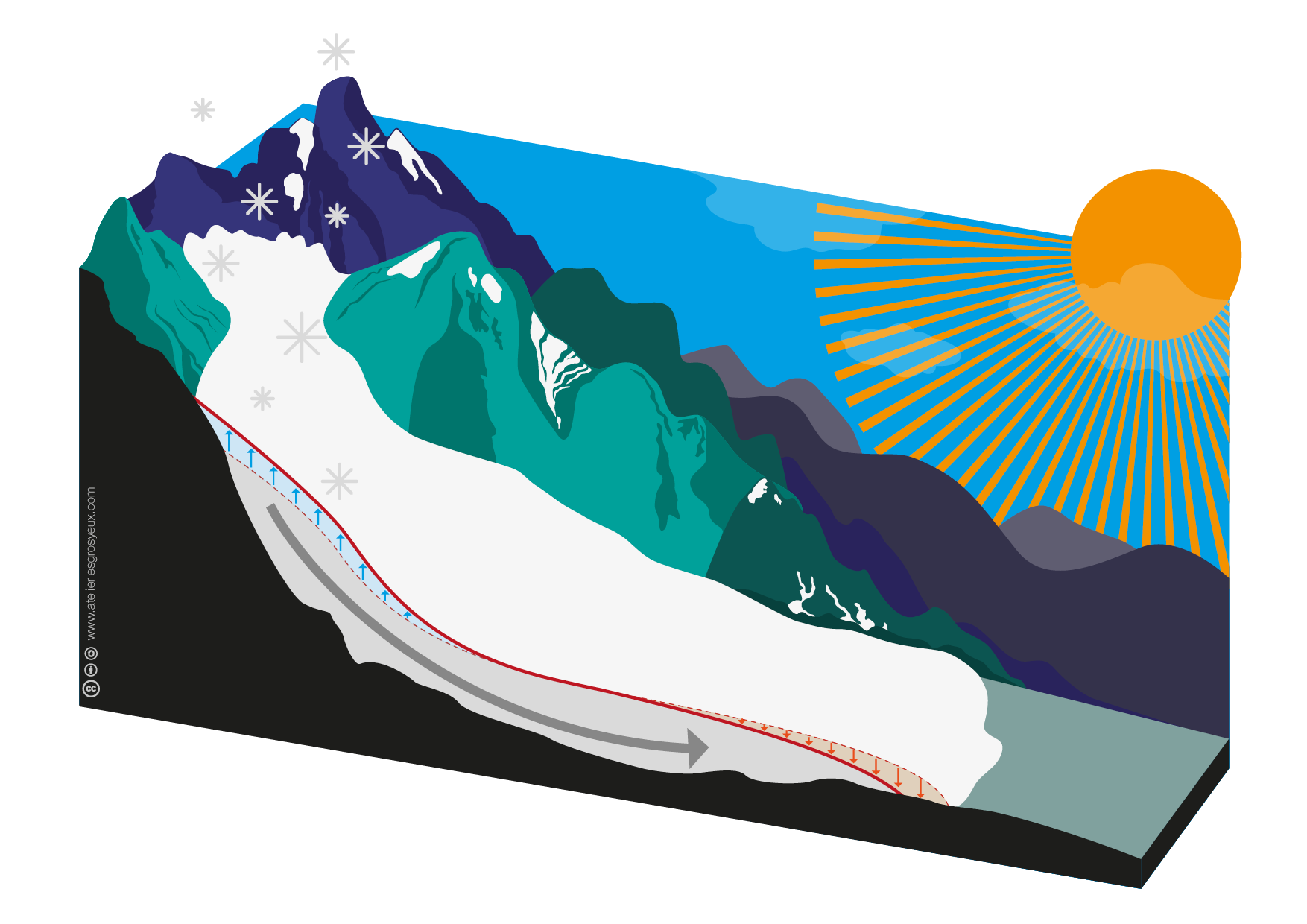

Now, let’s have a look at a glacier in OGGM.

OGGM glacier systems are highly heterogeneous: different numerical grids, simplifications in space (2D to 1D) and time (daily, monthly) scales, and incomplete data sources. OGGM is highly parameterized and calibrated: changing OGGM’s boundary conditions require re-calibration, which will have non-linear consequences on the entire system. For example, changing the precipitation correction scaling factor will lead to the same glacier mass-balance value (by design) but a different mass-balance gradient, therefore ice flux, ice thickness and re-calibrated ice creep parameter. Non glacier modellers will have a really hard time understanding what is going on under the hood with all these interlinked processes.

Of course, such non-linearities also exist in WRF. However, WRF is not calibrated as part of the modelling workflow (while it is a necessity in OGGM), and users have access to a large volume of independent validation data. In OGGM, practically all data available at large scales (and there aren’t many) are already used for calibration. There are no observations for the glacier interior or its base, and a lot of arbitrary decision-making process.

Because of this high level of parameterization and internal calibration, OGGM requires specific domain knowledge from its users. Misusing it may hide model errors quite effectively via calibration; if I’m honest, as a model developer I’m feeling very responsible when users struggle or (rightfully) criticize model internals.

It is reasonable to ask whether “user friendliness” really is that friendly, especially if it leads to silent or hidden mistakes.

Open source and academic careers

Is it fair to ask PhD students or post docs to spend a great deal of their time on software maintenance? When OGGM improves, who profits from it? I don’t know the answer to these questions, but as someone who spent a great deal of my time on open-source projects, I have a few pledges:

- Open science takes time! Scientific papers should be evaluated according to new standards: transparency and reproducibility of the analysis chain, availability of data/code and its documentation.

- Open source takes time! The work of open source developers should be acknowledged and should become an asset for academic jobs, not a handicap.

- Learning code takes time! Formal training at University and high-school curricula still not adapted to the challenges ahead - we have to close the gap and make everyone feel welcome in the open-source community, regarding of their coding level. Everyone can participate!