It maybe surprising, but the “dynamical core” of OGGM is only a very small part of the entire codebase. The numerical scheme we developed for OGGM is simple but flexible: it allows for arbitrary bed geometries and for transfer of mass from tributary flowlines. We rely on an adaptive time stepping scheme, making use of the CFL condition to decide on an appropriate time step.

Recently, our colleague and OGGM contributor Alex Jarosch pointed out serious flaws in our time stepping strategy: most notably, we used to enforce a minimal time step when the step required by the CFL condition was too small. This lead to instabilities, which I dealt with by implementing a very dirty “trial and error” time stepping that would first run an “ambitious” time step and re-rerun a less ambitious one when it failed with numerical errors. These ad-hoc solutions were developed at haste to “get the job done” in the early stages of OGGM development. Alex was right to point out that they were flawed and dangerous.

TL;DR: summary

After some thinking and a lot of empirical tests, I came to the following conclusions:

- we implemented a new, much cleaner scheme in OGGM, thanks to Alex’s suggestions (see the PR).

- the previous scheme was flawed, but did not yield significant or worrisome volume errors at the regional scale (< 1%). At the individual glacier level, errors could be left unnoticed and reach 15% for small glaciers (very rare).

- the new scheme is about 30% faster (!) than the previous one. This is due to a more accurate handling of instabilities (here too, prevention is better than cure as it seems)

- we are not yet 100% sure that the scheme is unconditionally stable. Empirical tests show promising results, but a full stability analysis is required. Because of the non-linearity of the section geometry update and the complexity of handling the mass transfer, this will probably never be possible.

TL;DR 2: what did you change?

A few lines of code, but with important consequences:

- the new default CFL factor is 0.02, instead of 0.05 before (which would then be changed to 0.01 in case of detected instabilities…)

- there is no “try and see if it works” algorithm any more: with CFL=0.02, the model runs stable. If the time step required to ensure stability is smaller then a threshold value (set to 60 seconds), the model with simply stop and error instead of “try and see”. In practice, this threshold is reached on a very small number of glaciers.

- users can control these two parameters if they want, like any other model parameter.

- the OGGM results will change, but likely “not too much”.

- the code is simpler.

Detailed analysis

Errors of the original algorithm

This is the first thing I wanted to know: how large are the errors we are making with our ad-hoc method?

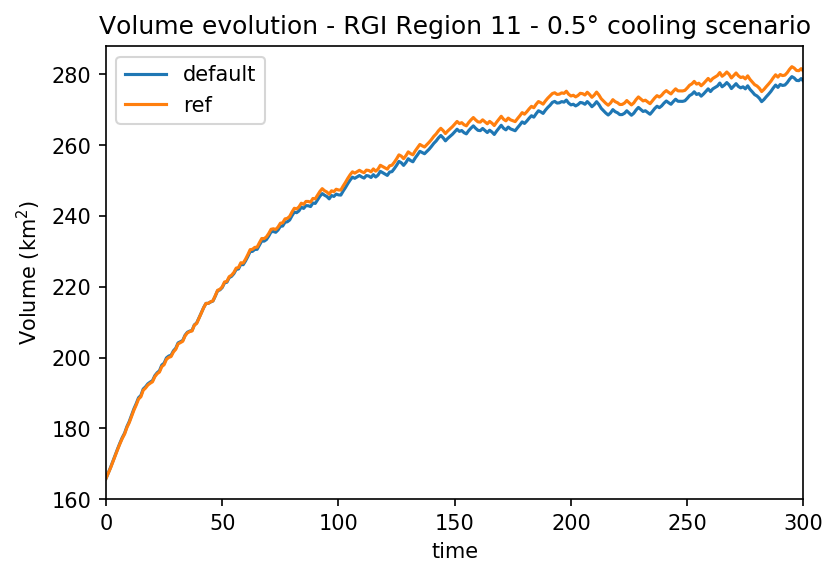

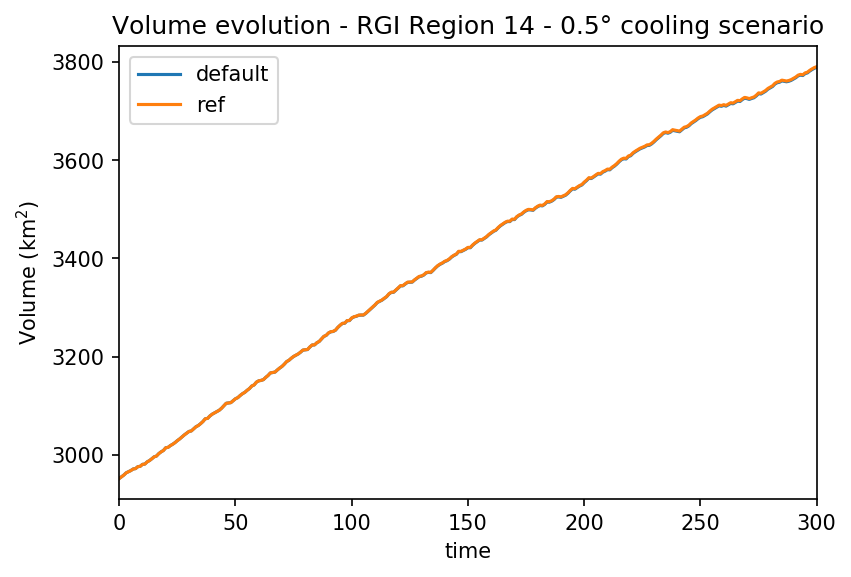

We test the original ad-hoc algorithm (“default”) with a reference run (“ref”) which uses a very small time step (CFL=0.005) and no trick. We run OGGM in a cooling scenario (more likely to exacerbate numerical errors) for two RGI regions: region 11 (European Alps, 3882 valid glaciers) and region 13 (Central Asia, 27727 valid glaciers):

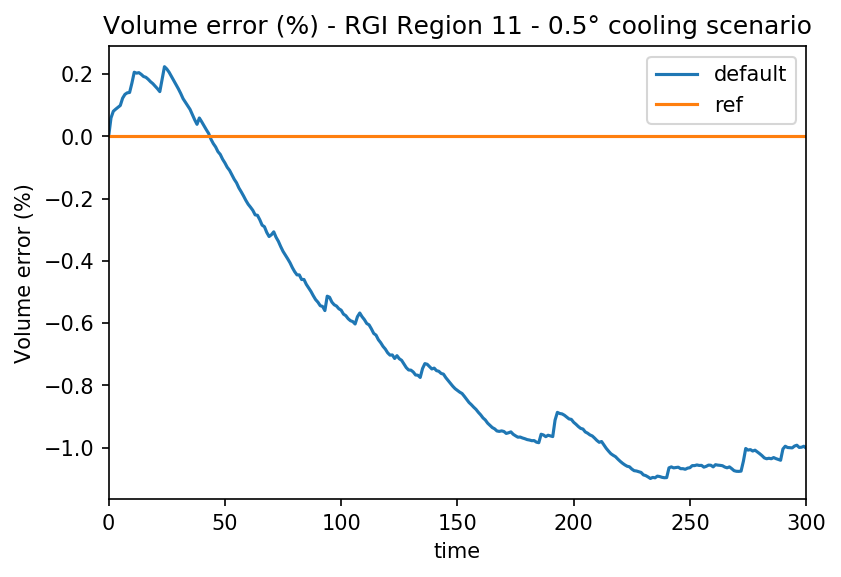

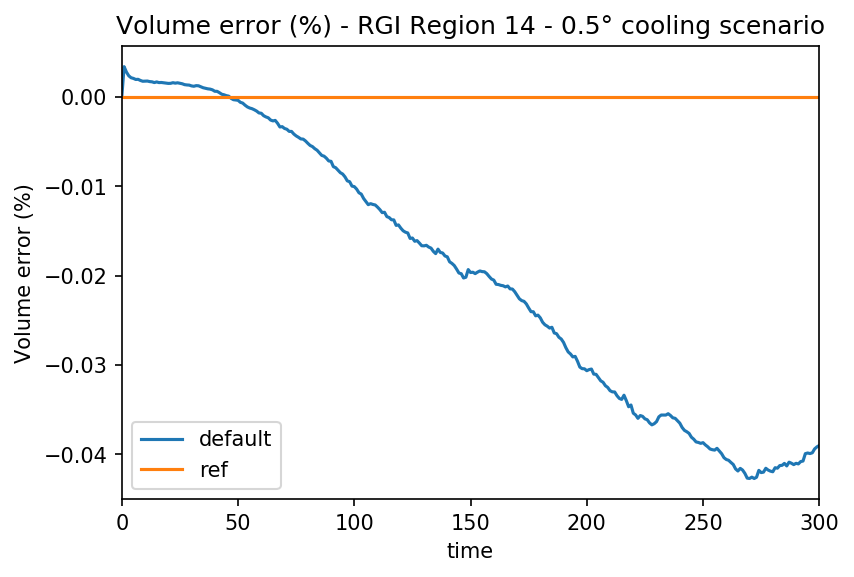

The differences between the two runs are minimal. RGI Region 14 has a much larger volume and much larger glaciers, explaining why they are far from equilibrium after 300 years. In terms of relative error, the differences are still significantly larger for the Alps:

The sawtooth curve pattern is characteristic of instabilities. The error for the Alps is about 1%: this is much smaller than many other uncertainties coming from e.g. the mass-balance models.

Choice of the “correct” Courant number

To decide on the time step, we use the famous formula:

$ \Delta t_{cfl} = C_{max} \frac{dx}{max(u)} $

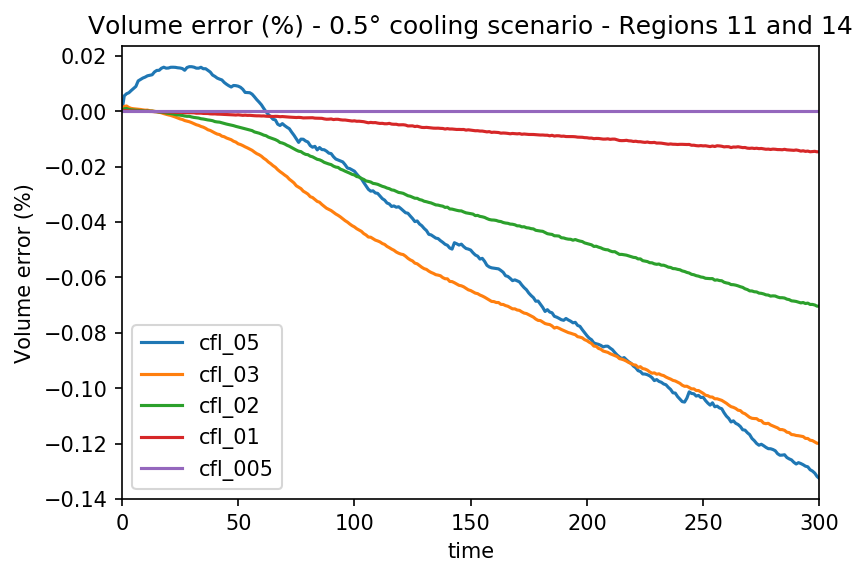

With $u$ the velocity, $dx$ the grid spacing, and $C_{max}$ the maximum Courant number ensuring stability. In our explicit scheme, $C_{max}=1$ is unstable. We run OGGM on the two same regions as above, with various values of $C_{max}$: 0.05, 0.03, 0.02, 0.01, 0.005 (the “reference run”). Here we shoe the total volume errors relative to the reference run for both regions combined:

When the Courant number is too large (0.05), the sawtooth pattern hints at numerical instabilities. For lower values, the difference to the reference run gets smaller and smaller. I don’t really know where the differences come from: I don’t know if there are real “instabilities” or an accumulation of floating inaccuracies or something else.

Based on these error curves, smaller Courant numbers would always be “better” of course. But at the same time, the differences are very small. We rely on other arguments to decide for the new default: number of run failures (“time step too small”) and performance. For these two measures, it appears that 0.02 is an excellent compromise, with the smallest number of errors altogether and an excellent performance.

Performance of the new scheme

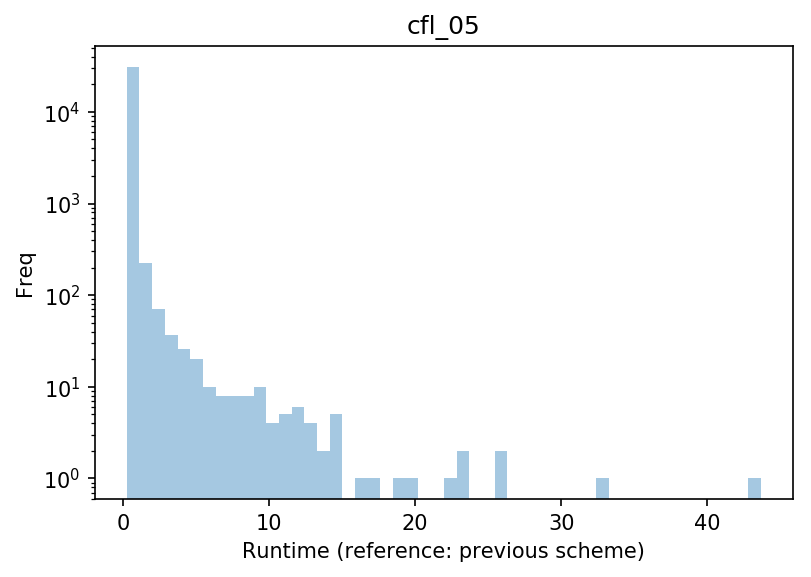

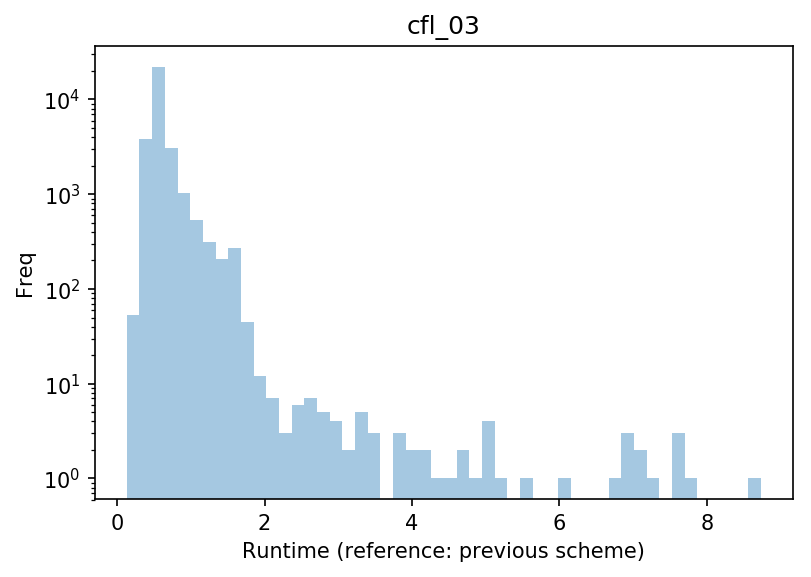

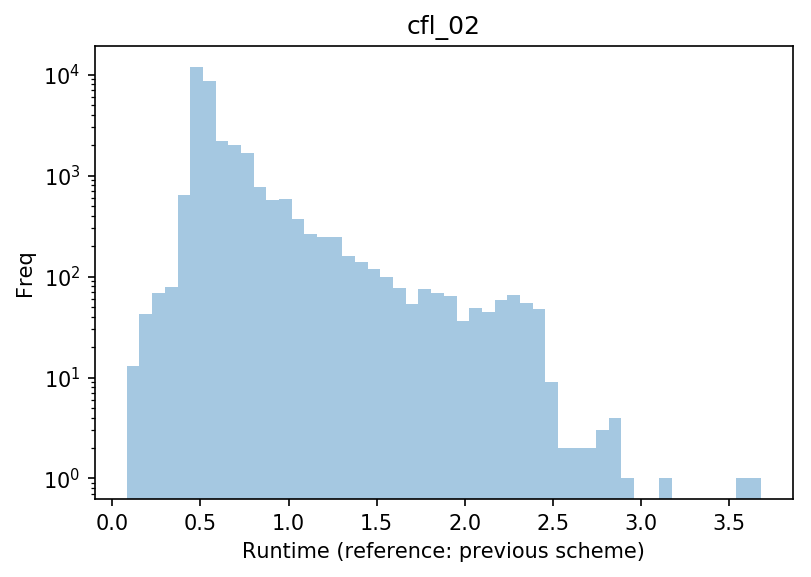

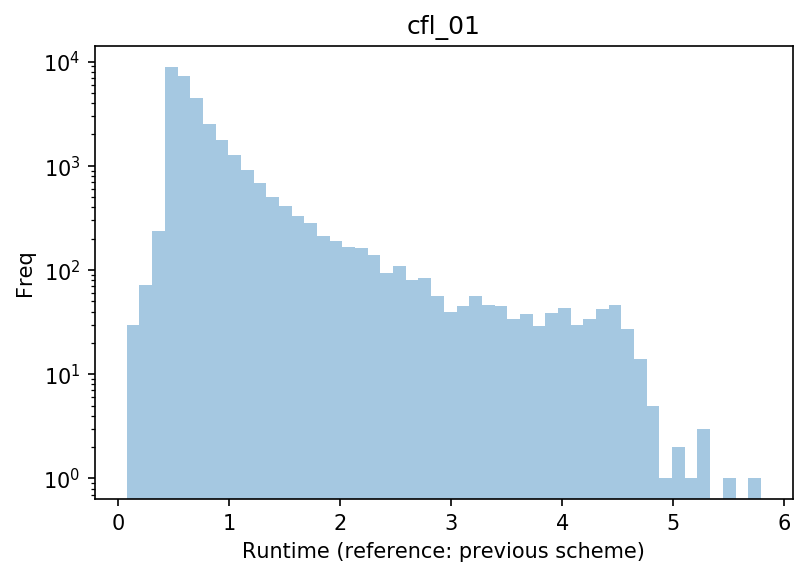

We measure the time taken to simulate each individual glacier, and compare it with the previous scheme. In the plot below, a value of 1 means “as fast as before”, and larger values “x times slower than before” (note the varying x axis ranges):

With $C_{max}$=0.05, which should be faster in theory, many runs take more than 10 times longer than before: this is due to the fact that this number is too high and generates instabilities, which the model then has a hard time “correcting”. With $C_{max}$=0.01, the model is often slower but without outlier. With $C_{max}$=0.02, the model runs fastest, with the smallest number of glaciers running slower than before.

With these new settings, OGGM can therefore be slower than before on some glaciers, but 92% of the glaciers run faster. On average, the model runs more than 30% faster! This is due to the rather stupid “try and error” algorithm which was used before, combined with undesired instabilities in the previous scheme.